Founders Perspctive

Explore: Wealth Planning Founder’s Perspectives Books

Is There a New Normal for Inflation and Interest Rates?

John Merrill, January 2024

We have experienced a dramatic seesaw in both inflation and interest rates since the onset of Covid.

Both inflation and interest rates plummeted in early 2020 in reaction to the steep drop in economic activity from the government enforced shutdowns and Covid-instilled fears.

In early 2021, inflation changed direction. It began to rise in reaction to shortages in goods that stay-at-home consumers demanded. The Federal Reserve (Fed) was slow to respond with higher rates in 2021, believing inflation was “transitory”…that it would end quickly when supply chains were repaired.

Yet when inflation continued its upward momentum into 2022, the Fed relented and began to raise rates in April of that year. Inflation peaked at over 9% in July of 2022, but the Fed, way behind the inflation curve, continued its steep rise in interest rates all the way to July of 2023. By then it was obvious that inflation was trending down.

This allowed the Fed to pause further rate increases and assess if they had already done enough. They have maintained their rate target of 5.25%-5.5% ever since. Until Chairman Powell’s press conference on December 13th, the Fed maintained a “hawkish” tone that it was ready to raise rates again.

At that meeting, Powell surprised the world by discussing rate cuts in 2024. It was an indication that holding rates above 5% for much longer may do more harm to the economy than good for inflation.

Throughout this entire seesaw of inflation and interest rates, the Fed predicted that the long-term neutral rate was 2.5%. In other words, once this bout of inflation is in the rear-view mirror, the Fed Funds rate would likely average around this level.

A base rate of 2.5% is 0.5% above their inflation target of 2%. This spread over inflation is close to its average spread since 1926 according to Stocks, Bonds, Bills, and Inflation Yearbook (2023). This would provide a return slightly greater than inflation yet not be so high as to discourage economic activity.

Of course, the rate would likely go much lower during periods of economic stress and much higher in periods where the economy is growing well above its non-inflationary potential.

With a stable base rate of 2.5% on short-term deposits, bond yields should also normalize. In other words, yields on Treasury bonds would increase as maturities lengthened. Again, turning to Ibbotson, a normal spread for the benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury bond would produce an average yield of just above 4% if the base rate was 2.5%. (As noted in our December 2023 Commentary, the long-term average of that bond since 1790 is 4.35%!)

All of this hinges on the Fed hitting its inflation target of 2% (on average). How realistic is that? After all, the Fed could not get inflation up to its 2% target for over a decade before Covid (it hovered between 1% and 2%). Then, it went way above its target with the dislocations of Covid. Inflation peaked in mid-2022 and has trended down ever since.

While there are no guarantees, there is room for optimism that the 2% inflation target will be more easily met over the next decade than it was over the last.

In my Perspective, Inflation and Interest Rates (January 2021), I noted the three forces that restrained inflation over the prior decade were demographics, digitization, and globalization. These were powerful deflationary forces in that prior decade.

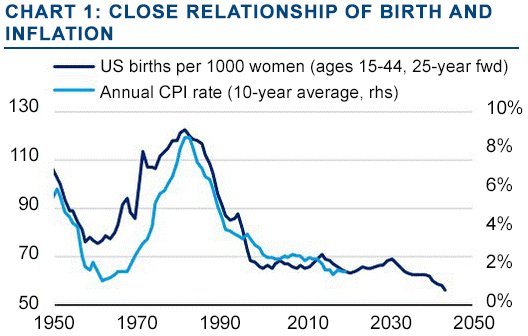

Source: The Wall Street Journal, BofA Research Investment Committee, Haver

Both demographics and digitization (technology, including AI) remain potent deflationary forces. Chart 1 illustrates the close relationship over time between the US birth rate and the inflation rate (averaged over 10-year periods).

On the other hand, globalization has greatly diminished in favor of re-shoring and near-shoring. While this new direction is overdue to secure needed resources, the higher costs associated with these are inflationary.

Other longer-term inflationary forces have arisen in the last several years including higher real wages and the costs of mitigating climate change. (Keep in mind that most of the costs of building a renewable energy source to replace an existing fossil fuel energy source are inflationary. They do not add to ec1onomic output, they simply replace what already exists.)

In other words, there may be a balance between inflationary and deflationary forces that gives rise to a slightly higher but stable inflation rate (2%) in the future. This would allow for the interest rate picture that the Fed envisions.